The year 2020 saw two important books approaching Hinduism in the United States from an empathetic, yet academic point of view.

One is the already-reviewed

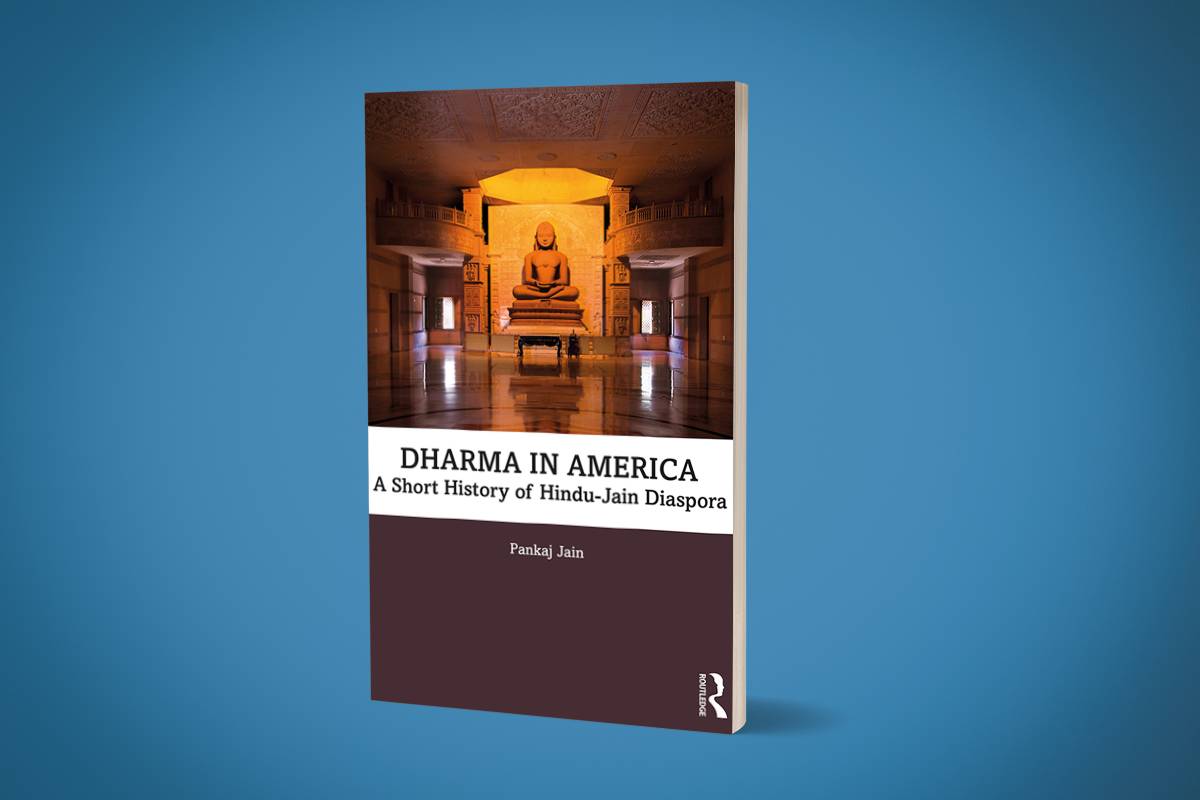

Hinduism in America by Prof. Jeffrey Long and another, which is currently getting reviewed here, is Pankaj Jain’s

Dharma in America: A short history of Hindu-Jain Diaspora

While Dr. Jeffrey Long is an American who has moved towards Dharmic religious traditions, particularly Sri Ramakrishna's Vedanta, Pankaj Jain came to New Jersey in 1996 on a H1B visa and is now Associate Professor of Philosophy and Religion at the University of North Texas.

How did a software professional end up becoming an academic on religion?

His Indian employer gifted two American software experts, who had come to teach Pankaj Jain and his colleagues a programming language, ‘a copy of the Bhagavad Gıta, and a few albums of Indian classical music’ and this, Jain says, was his ‘first wake-up alarm.’ (p.vii)

The book skilfully combines his own personal journey with the larger history of how the Dharmic family of religions came to the United States and created an impact, faced challenges, adapted, survived and are flourishing.

Though there have been quite a lot of books on Hindus in the United States, he points out that most of these books do not study ‘Indian classical music or Ayurveda making inroads into the Americas.’ (p.2)

It is interesting to note that the image of India — from being a land of ‘peculiar deities’ and exotic animals during the period when the United States was under British dominion — changes to that of a philosophical, ancient nation, through the transcendentalist movement.

By 1847, at Harvard Library, Emerson was reading the translations of Ramayana and Mahabharata as well as books on ‘Hindoos’ published by Serampore Mission Press.

Ram Mohan Roy was also an influence on Emerson in his pursuit of Hindu knowledge, brings out Jain, and considers Roy ‘as one of the ancestors of the Transcendentalists’ (p.13).

He gives the readers a brief tour of the influence of Vedantins, starting with Swami Vivekananda, and that of the theosophists, and mvoes to later-day gurus like Rajneesh Chandra Mohan (‘Osho’).

With a bird’s eye-view of the conceptual and exotic influence Hinduism had on the Americas, he moves to the way indentured labourers in the Caribbean islands contributed to societal evolution there.

Hindus comprise the second largest religious group after Christians in Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, and Suriname.

In Guyana, Hindus as indentured labourers had come in 1838, and by 1870, there was at least one temple which was then decades old.

The book also brings out interesting political developments as the colonised people started asserting their rights.

Here is a very interesting fact from the book.

In 1906, there was a ‘Pan-Aryan Association’ in the United States. No, it was not a white supremacist organisation. Actually, it was co-founded by Mohammed Barkatullah (president) and Samuel Louis Joshi, and their inspiration was Shyamji Krishna Varma.

The movement was for the cause of Irish revolutionaries (p.19).

So, even in the early 20th century, Indians have been using the term Aryan in their own traditional, non-racial way, to fight for human rights, transcending racial and religious barriers.

The book highlights, in the chapter on the freedom movement, the ‘Hindu German Conspiracy’ and the Ghadar movement, among others.

The ‘Hindu German Conspiracy’ trial held in San Francisco between November 1917 and April 1918 was a blow to US-based activities of Indian revolutionaries.

Yet, it helped sensitise American public opinion and to an extent, move it in favour of Indian Independence.

The New York Times, now a promoter of stereotypes of cultural racism against India, then even published an article by Lala Lajpat Rai, which argued the case of Indian freedom based on the values of liberty and democracy (p.22).

As said earlier, the book specifically deals with three important aspects — usually not discussed in other books on the same subject — the way Ayurveda has entered mainstream American culture, the influence of Indian music and the Jains in the US.

From the initial hardship of Indian physicians, to the establishment of AAPI (the American Association of Physicians of Indian Origin) in 1982, to Deepak Chopra becoming a byword for holistic medicine (or quackery, depending on from which side of the fence you look at him) in the United States, Jain traces the impressive evolution of Indian physicians in America and the change their presence brought to the US cultural mosaic.

He describes the work of Navin Shah — 'one of the critical co-founders of AAPI' — (Ujamal Kothari was the founding president), who toiled hard against the discriminations Indian doctors faced at various planes — from the workplace to housing access — and how he created a lobby among others.

Jain reveals that it was the high demand for doctors during the Vietnam war that made then then US President, Lyndon Johnson, allow a large influx of doctors the privilege of US citizenship.

Many prestigious institutions such as the Mayo Clinic, the Cleveland Clinic, Brigham, Massachusetts General Hospitals of Harvard, Mount Sinai of New York, Cedars Sinai of Los Angeles — that once were dominated by “White” physicians — now have Indian Americans in top leadership positions.

(p.27)

The Ayurvedic impact, he describes, is quite interesting.

From one of the Ayurvedic pioneers, Vasant Lad, who came to the USA in 1979, to the present-day numerous organisations and American personalities, he also observes that ‘Ayurveda did not flourish in the Indian American communities, unlike Chinese medicine that continues to thrive in the Chinese communities.’ (p.36)

There are also legal issues with respect to practising Ayurveda in the United States:

Today, although nine American states — Oklahoma, Idaho, Minnesota, Rhode Island, California, Louisiana, New Mexico, Arizona, and Colorado — have a Health Freedom Law to allow unlicensed, traditional healthcare practitioners, licensing is still needed to protect the reputation of Ayurveda.

(p.37)

The National Ayurvedic Medical Association (NAMA) was formed in 1998 for Ayurveda practitioners in the US and got incorporated in 2000.

Then, he discusses how Indian cuisine is also penetrating into the American food culture, and subsequently moves to Indian classical music (ICM) and Hindu devotional music. The person who brought ICM to the United States was Sufi Veena player Hazrat Inayat Khan (1882–1927).

The pioneers who brought ICM were such giants like Rabindranath Tagore, Udhay Shankar and of course Pandit Ravi Shankar.

The performance of M.S. Subbulakshmi at the United Nations, transplanting Tyagaraja Utsavam to Cleveland etc. all form part of this narration. ICM has its influence on jazz music too. With the impact of great masters like Ali Akbar Khan and Amjad Ali Khan (sarod), Bismillah Khan (shehnai), Nikhil Banerjee and Imrat Khan (sitar), Ram Narayan (sarangi), Zakir Hussain (tabla), Carnatic artists T. Viswanathan (flute), T. Ranganathan (mridangam), and M.S. Subbulakshmi (voice), the components of ICM are increasingly heard in jazz, pop, and rock music. However, for most Western audiences, ICM performers remain exotic and rare, he writes (p.54).

With respect to devotional music, though kirtan is a part of the Sikh religion as well as the Hare Krishna movement, the main focus of Pankaj Jain is the bhajan — particularly as conducted in the Mata Amritanandamayi movement in the United States.

The author could have added a little more about John Coltrane and how his wife Alice Coltrane (1937-2007), who was also a musician, took a great interest in Hindu Dharma and became Turiyasangitananda or Turiya Alice Coltrane.

Her guru was Sri Sathya Sai Baba, whose movement also has as bhajan as an integral part.

Then there is quite a lengthy chapter on Jains in the United States. It is detailed and goes into this microscopic, minuscule community within the Indian diaspora which itself makes up only one per cent of the US population.

The book discusses in detail the Jain history, its arrival and taking roots in the US, Jain diamond traders and Jain values in the US.

As of 2019, the Jain population in the United States and Canada stands at more than 150,000 and is growing. There are currently about 70 Jain temples in North America.

Naturally, studies of Jainism have thus become important with the growing Jain population seeking to establish academic centres.

In the appendix, he provides 16 universities in the US which provide Jain Studies as an academic programme.

Of these, one particular centre caught the eye of the present reviewer — a graduate level programme in Jainism at Claremont School of Theology (CST).

This was incorporated in 2014 after Claremont Lincoln University in California had signed a three-year contract to teach Jainism in 2011.

But soon, CLU closed its religious study programme and hence the course was moved to CST, the parent body of CLU (p.82).

Now, CLT may be ‘ecumenical and interreligious in spirit’ as their website says, but it is also involved in cross-cultural evangelism. The mission statement puts it nicely, but precisely:

Students are nurtured by scripture, tradition, experience, and reason and are prepared for lives of ministry, leadership, and service. Graduates are prepared to become agents of transformation and healing in churches, local communities, schools, non-profit institutions, and the world at large.

And establishing a Jain centre there with money from Jains seems to be driven by an ulterior motive to train the missionaries in Jain Dharma and society so that they can ultimately convert the Jains.

Of course, the Jains who fund the programme may not be aware of such missionary intent, and the 'transformation' programme may not even happen now.

But ultimately, that will be its final aim.

Meanwhile, after the publication of the book, over two dozen families, individuals and foundations have come together to create a joint Endowment Chair in Jain and Hindu studies at California State University, Fresno.

The Jain and non-Jain Hindu communities coming together for such an academic programme is because of a 'mutual commitment to educating current and future generations of students about the principles of nonviolence, dharma (virtue, duty), justice, pluralist philosophy, interconnectedness of all beings and care for the environment through Hindu-Jain texts, philosophies and traditions', according to the University press release.

Jain adaptations to the US environment manifest in views such as non-performance of daily rituals, and asceticism being viewed as a 'core aspect' of Indian Jainism, among other justificatory beliefs such as American 'acceptance' of all Jain denominations and the rise of American Jain women in leadership roles in Jain organisations at local and national levels. (p.82)

In connection with Jain influence, one misses in the book a section on the phenomenon called Rajneesh Chandra Mohan alias Acharya Rajneesh alias Bhagwan Sri Rajneesh alias Osho — who might not have been a practising Jain (he was a strict vegetarian though) — but was born into a Jain family.

Should the phenomenon of Rajneesh with the sordid Oregon episode be considered part of the Jain legacy?

Whether it is 'Jain legacy' or not, Rajneesh, as a phenomenon which combined pop-spirituality, exhaustive coverage of all world mystic masters and a certain amount of charlatanism, has to be studied by Dharmic scholars.

The Indian diaspora also adds an economic dimension to the competitive global ecosystem.

The author points out:

The Indian diaspora, the largest diaspora in the world, as noted earlier, is also responsible for making India the first country in the world to receive remittances amounting to more than $80 billion from around the globe, according to the Migration and Development Brief by the World Bank in 2018.

(p.104)

Overall, members belonging to the Hindu family of religions, whether they adhere to them or not, are growing in number in the West. Compared to Muslims or Jews, they are miniscule. But they have a potential for great cultural and value-system impact.

While this is good at one level, at another level, they will be seen as a threat — just as how Jews were seen once.

For almost 2,000 years, antisemitism was axiomatic to the West.

A society so entrenched in hatred as part of its civilisation is now deprived at least explicitly of Jews as hate-objects.

Anti-Semitism has terrible socio-political costs. So, what does a civilisation so obsessed with institutionalised, axiomatic hatred do?

It has to discover newer objects of hatred and justify the hatred. For that, the West has discovered the Hindus and the caste-libel to justify this hatred.

The institution of hatred has evolved such that unlike in the case of the Jews, the West can 'recruit' Hindus themselves into the obliterative project.

Will this hatred that we see in articles of the New York Times and Washington Post become a full-blown hate phenomenon like what happened in Germany of the 1940s under the contemporary circumstances?

Though the author does not touch this dimension, even as he discusses instances of isolated hate crimes, buried in the footnotes of the chapter ‘Indian Americans and civic engagements’ is a hint.

What the lengthy footnote as a whole reveals is an important caution. The excerpt from it given here shows how ominous it gets as the civic Hindu engagements in US start becoming more pronounced:

Tulsi Gabbard (D-HI), the first Hindu elected to the U.S. Congress, who has no Indian ancestry, nevertheless is pelted by racist and anti-Hindu bigotry during every election cycle. Just last month, before Gabbard handily won a primary challenge, she was targeted by an internet portal, infamous for its voluminous efforts to force American cities to take down statues celebrating Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violence movement, for having met with Modi.

(p.101)

On the whole, the book is an engaging read — a must for students of Hindu civilisation who want to understand the socio-cultural dynamics of the Hindu-Jain diaspora in America and the importance they have for the future of Dharma.

Source: Swarajya

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.